learning is ecpc…

-

![]()

Feedback is a gift

Feedback is a gift, you can do three things with it:

- not accept it

- accept it but not use it

- accpet it and use it

The real value of feedback lies not in hearing it, but in what you choose to do with it. Whether it’s praise or constructive critique, feedback provides a window into how others perceive your actions, decisions, and impact. Choosing to engage with it thoughtfully can accelerate personal growth, deepen self-awareness, and improve performance. But it takes courage to look at yourself through someone else’s lens and even more to act on what you see.

In my practice, I facilitate feedback sessions with intention and care. I create safe, structured environments where individuals feel heard, respected, and supported. Whether working with elite athletes, developing military leaders, or mentoring coaches, I ensure feedback is timely, specific, and rooted in shared goals. I encourage two-way dialogue—balancing challenge with empathy—and guide participants to reflect, identify actionable takeaways, and build development plans. Over time, this builds trust, resilience, and a culture where feedback is not feared but welcomed as a driver of continual improvement.

-

![]()

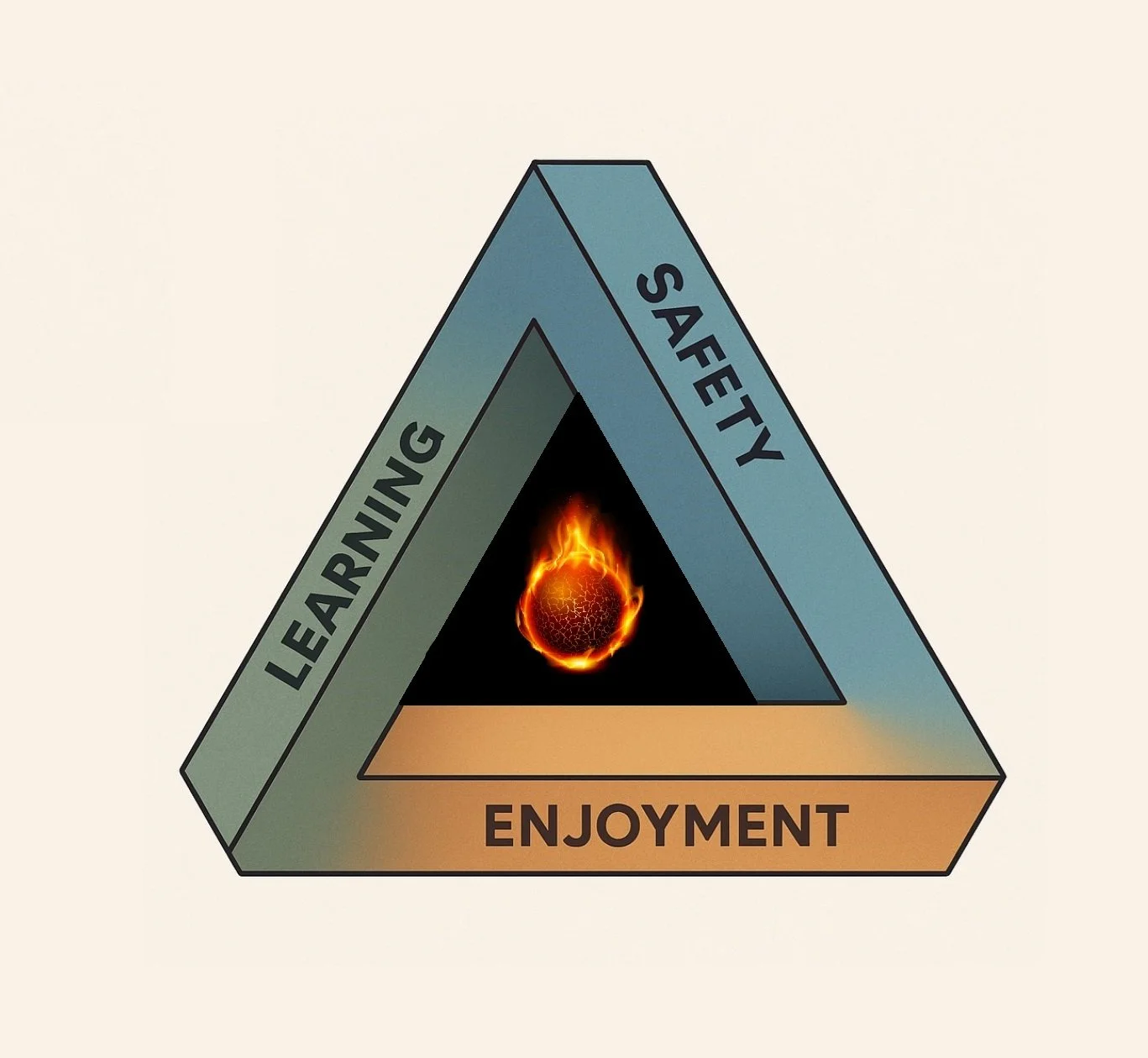

Components of a successful experience

Like the fire triangle, which requires heat, fuel, and oxygen to sustain a flame, a safe and productive day in any learning or performance environment requires three interconnected elements: Safety (physical and psychological), Enjoyment, and Learning. If any one of these is missing, the integrity of the experience collapses—just like a fire can’t burn if one element is removed.

1. Missing Safety (Physical or Psychological)

Learning is blocked because individuals operate in survival mode—focusing on avoiding harm rather than absorbing information or improving skills.

Enjoyment evaporates as anxiety, fear, or discomfort replace engagement.

The overall culture suffers, and long-term participation or progress is compromised.

2. Missing Enjoyment

Learning is limited as motivation wanes—learners may comply but not commit.

Safety may be undermined subtly, especially psychological safety, as learners feel like tools for output rather than valued individuals.

Without enjoyment, enthusiasm and creativity fade, and burnout or disengagement sets in.

3. Missing Learning

Enjoyment may be high in the moment but lacks deeper fulfillment, people get bored and the other elements are comprimised.

Safety can be at risk if participants aren’t taught essential skills or decision-making processes.

The absence of purposeful learning means limited personal growth or transfer of value to future contexts.

-

Reflection drives perfection

True excellence isn’t just about action—it’s about purposeful, reflective action. The phrase “plan the work, work the plan” reminds us that success is rarely accidental. It’s built on clarity, preparation, execution, and reflection. Before we dive into any challenge, we need a clear understanding of the task ahead—because charging forward without thought is often the quickest route to failure. One of the most powerful metaphors for this is scouting a river before paddling it.

Before launching into fast-moving water, an experienced paddler doesn’t just jump in—they scout the river. They ask: Where are the hazards? Where are the rocks, the drops, the strainers? Where are the eddies—the safe zones where I can pause or recover? If I do nothing, where will the current take me? Is that where I want to go—or is it pulling me somewhere dangerous? These questions form the foundation of the plan. Just like in life, sport, or leadership, the river always flows, and if you don’t plan your route, you’ll be taken on one anyway—whether you like it or not.

Once the route is chosen, the paddler commits to the plan. But it doesn’t end there. Even while navigating the river, they remain alert, reflecting in real time: Is this going as expected? Do I need to adjust? Can I make this feel smoother, safer, more controlled? Post-run, they review what worked, what didn’t, and what to change next time. Over time, this blend of planning, execution, and reflection builds mastery. It’s not about avoiding all risk—it’s about understanding it, preparing for it, and making informed, adaptive decisions.

In the same way, reflection helps us see where we’re drifting, where we need to steer more intentionally, and how to build in moments of control and safety along the way. Whether you're navigating white water or the pressures of performance, take the time to scout your river, choose your line, and commit to your stroke—then reflect, refine, and go again. That’s how reflection truly drives perfection.

-

![]()

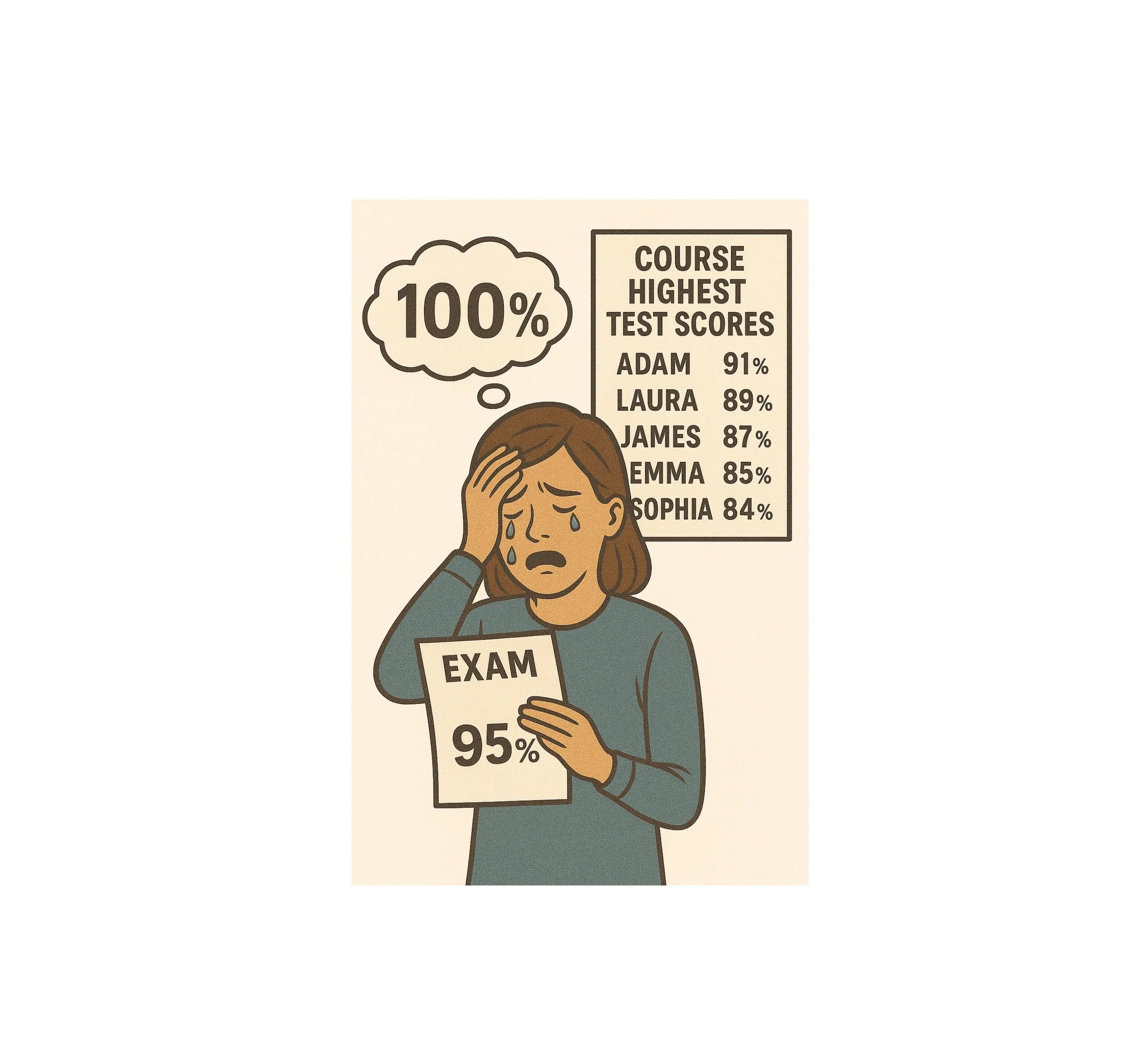

Don't let excellence come in the way of good

Striving for excellence is valuable—but only when it serves progress, not perfection. Excellence should be a direction, not a destination. When it overrides action, learning, enjoyment, or sustainability, it becomes a barrier, not a benefit.

Instead, success often comes from consistent effort, honest reflection, and small improvements—done well enough, often enough.1. Perfection Paralysis (Analysis Paralysis)

When excellence becomes perfectionism, people can become so focused on getting everything exactly right that they struggle to take action at all.

Example: A coach might spend so much time fine-tuning session plans that they delay implementation, missing valuable coaching opportunities.

Outcome: Momentum is lost, deadlines pass, and real progress never begins.

2. Fear of Mistakes or Looking Imperfect

An obsession with excellence often fosters fear of failure or criticism. People avoid risks or uncomfortable growth moments because they fear it won’t be “excellent.”

Example: An athlete might avoid trying a new skill in front of others because they don't want to look bad.

Outcome: Growth is stifled, and confidence diminishes over time.

3. Burnout and Unsustainable Effort

High standards, when not matched with compassion or rest, can lead to exhaustion and disillusionment.

Example: A teacher or team leader who constantly works late, chasing the “perfect” outcome, may burn out and become disengaged.

Outcome: Performance drops, relationships suffer, and even basic success becomes out of reach.

4. Missing the 'Good Enough' Threshold

Success often requires consistency and progress, not perfection. Focusing only on excellence can cause people to overlook opportunities that are “good enough” to build momentum.

Example: A team rejects a solid plan because it isn’t ideal, waiting for a perfect solution that never comes.

Outcome: They fall behind more agile competitors who act, adapt, and improve iteratively.

5. Damaged Relationships and Trust

A relentless pursuit of excellence can come across as critical or unrelenting, damaging psychological safety.

Example: A leader who constantly corrects minor errors in pursuit of “excellence” may demoralize their team.

Outcome: Creativity dries up, morale drops, and people disengage or leave.

-

![]()

Why things don't happen

All issues in performance or progress come down to a simple distinction: "can't do" versus "won't do" — in other words, skill vs will.

A "can't do" problem arises when someone lacks the necessary knowledge, training, or resources to complete a task. It's a capability issue that requires support, development, and tools to fix. On the other hand, a "won’t do" problem stems from low motivation, unclear purpose, lack of ownership, or misaligned values. It’s not about ability but about attitude and engagement.

The key to driving meaningful change is accurately diagnosing which type of issue you're dealing with. Applying training to a "won’t do" problem wastes time, while pushing accountability on a "can’t do" problem causes frustration. Lasting solutions come from responding with the right approach: build skill where it’s missing, and build will where it’s lacking.

-

![]()

Choice and learning

At the core of everything we do lies a powerful truth: we all have a choice, and we all make those choices to feel good about ourselves. Whether it’s stepping up to a challenge, staying silent, helping others, or walking away, our actions are driven not just by logic or necessity—but by how they align with our sense of self. We constantly weigh the consequences of our decisions, consciously or unconsciously asking, Will this make me feel capable, respected, in control, valued? Or will it leave me feeling exposed, inadequate, or judged? Even when we avoid something, it’s often because doing nothing feels emotionally safer than the risk of getting it wrong.

Others can support us on this journey—offering tools, encouragement, and insight—but ultimately, we must learn to make and own our choices. No one else can walk the path for us. Coaches, friends, or mentors can guide us, but we have to do the work, face the discomfort, and commit to the actions that align with who we want to become. Growth happens when we accept that while help is available, the decision to act—and the reason for doing so—must come from within.

When we understand that everything we do is, in some way, an attempt to feel good about who we are, we begin to reflect more honestly. Are we choosing what’s easy or what’s meaningful? Are we doing this to grow—or to protect our self-image? Real progress begins when we take responsibility for our choices, act with intention, and build a self-image based on integrity, effort, and self-awareness—not just comfort or validation. Because in the end, how we feel about ourselves isn’t a byproduct of what we achieve—it’s the result of how we show up, day after day, by choice.

-

![]()

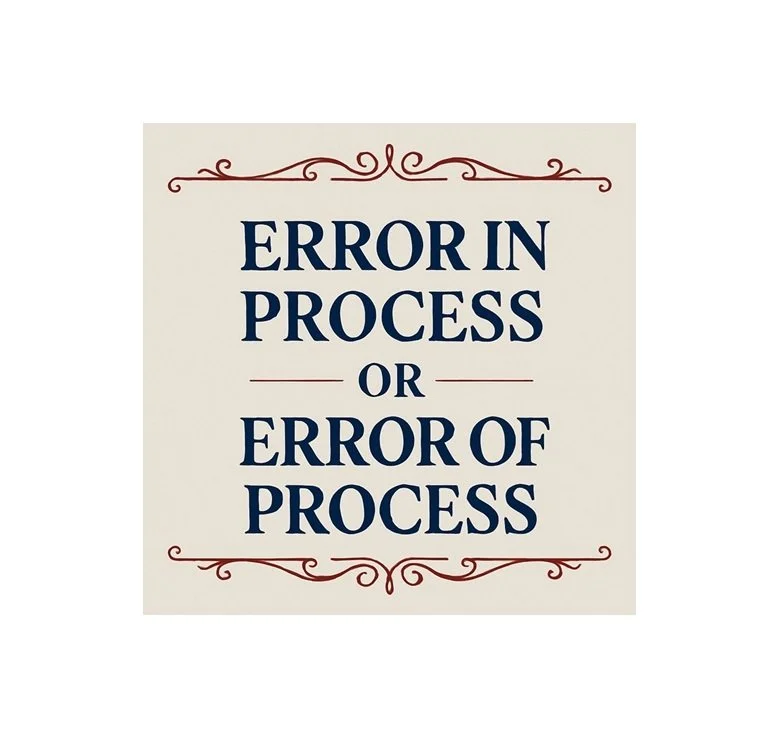

Which error was made

Understanding the distinction between an error of process and an error in process is essential for effective problem-solving, performance improvement, and leadership.

An error of process indicates a deeper, strategic flaw—selecting an inappropriate method, pathway, or plan that was never fit for purpose. It reflects a lapse in judgment, planning, or alignment with goals. On the other hand, an error in process suggests that the chosen approach was fundamentally sound but was compromised by how it was carried out—perhaps due to poor communication, lack of training, insufficient resources, or human error.

In a high-performance context, this difference can be the dividing line between addressing a systemic issue or simply fine-tuning operations. For example, if a team fails to meet its objective because it pursued the wrong objective entirely, that’s an error of process. But if the objective was right and the strategy sound, yet the execution faltered, that’s an error in process. In leadership and coaching, misdiagnosing one for the other can lead to unnecessary overhauls or missed opportunities for growth. Both require different remedies—errors of process call for a re-evaluation of purpose and alignment; errors in process demand focus on skills, systems, and accountability.

-

![]()

Preperation & execution

Preparation doesn't guarantee success—but it significantly increases the chance of it. Combining thoughtful preparation with strong execution is the most reliable route to consistent performance. Conversely, neglecting either element—especially both—leads to predictable failure.

The saying “Failing to prepare is preparing to fail” highlights the foundational importance of preparation in any task or endeavour. Preparation sets the conditions for success, but it must be paired with effective execution. The relationship between preparation and execution can be broken into four key combinations:

Good Preparation & Good Execution (Best Case)

– This is the ideal scenario. Strong planning, rehearsal, and forethought are followed by disciplined and skillful delivery. The outcome is usually success or excellence.

Example: A team that trains thoroughly and follows the game plan effectively performs at their peak under pressure.Good Preparation & Poor Execution

– All the right groundwork is laid, but mistakes or underperformance during delivery undermine the result. While disappointing, the preparation still provides a learning platform and can reduce the impact of failure.

Example: A student studies well but panics in the exam and underperforms.Poor Preparation & Good Execution

– Sometimes natural talent, improvisation, or luck can lead to a positive outcome even without preparation. However, this is unreliable and rarely repeatable. Success here is fragile and unsustainable.

Example: A speaker who hasn’t rehearsed still delivers a good presentation due to charisma and experience—but can't guarantee the same next time.Poor Preparation & Poor Execution (Worst Case)

– This is the clearest path to failure. Without proper groundwork and with poor performance in the moment, the result is predictably negative.

Example: Turning up to a match untrained and playing poorly leads to a predictable loss. -

![]()

Same Path, Different Craft: Tailoring the Journey to You

Each of us is travelling our own journey, even if we appear to be heading in the same direction as others. A powerful way to visualise this is through the example of someone paddling a stand-up paddleboard (SUP) alongside someone in a kayak. Both are navigating the same river or coastline, with the same destination in mind. They might both use paddles, understand water conditions, and face the same weather, currents, or obstacles. Yet, the way they experience that journey—the physical demands, techniques, and perspective—are fundamentally different.

The SUP rider stands tall, constantly adjusting for balance, exposed to wind and requiring core stability and footwork. They can see further, spot hazards earlier, but are more vulnerable to falling and fatigue from standing. The kayaker, seated and more stable, uses different muscle groups, has a lower centre of gravity, and can often paddle faster or longer with less physical strain—but has a more limited view and must rely more on instinct or experience to react to changing surroundings. If both used exactly the same technique, one would quickly become inefficient or even unsafe. Their shared knowledge—of water safety, stroke mechanics, navigation—must be adapted to their own craft.

This is the essence of individual development. We can follow the same principles—discipline, goal-setting, resilience, learning from failure—but how we apply them depends on our own strengths, challenges, environments, and experiences. Just like the SUP and the kayak, the tools we use, the support we need, and the rhythm we paddle at must suit our own journey, not someone else’s.

Comparing yourself to someone in a different "craft" can be misleading and unhelpful. Instead, the focus should be on understanding your own setup, refining your own technique, and moving forward with awareness. Success isn’t about keeping pace with others—it’s about progressing with purpose and self-awareness, in a way that’s right for you.

-

![]()

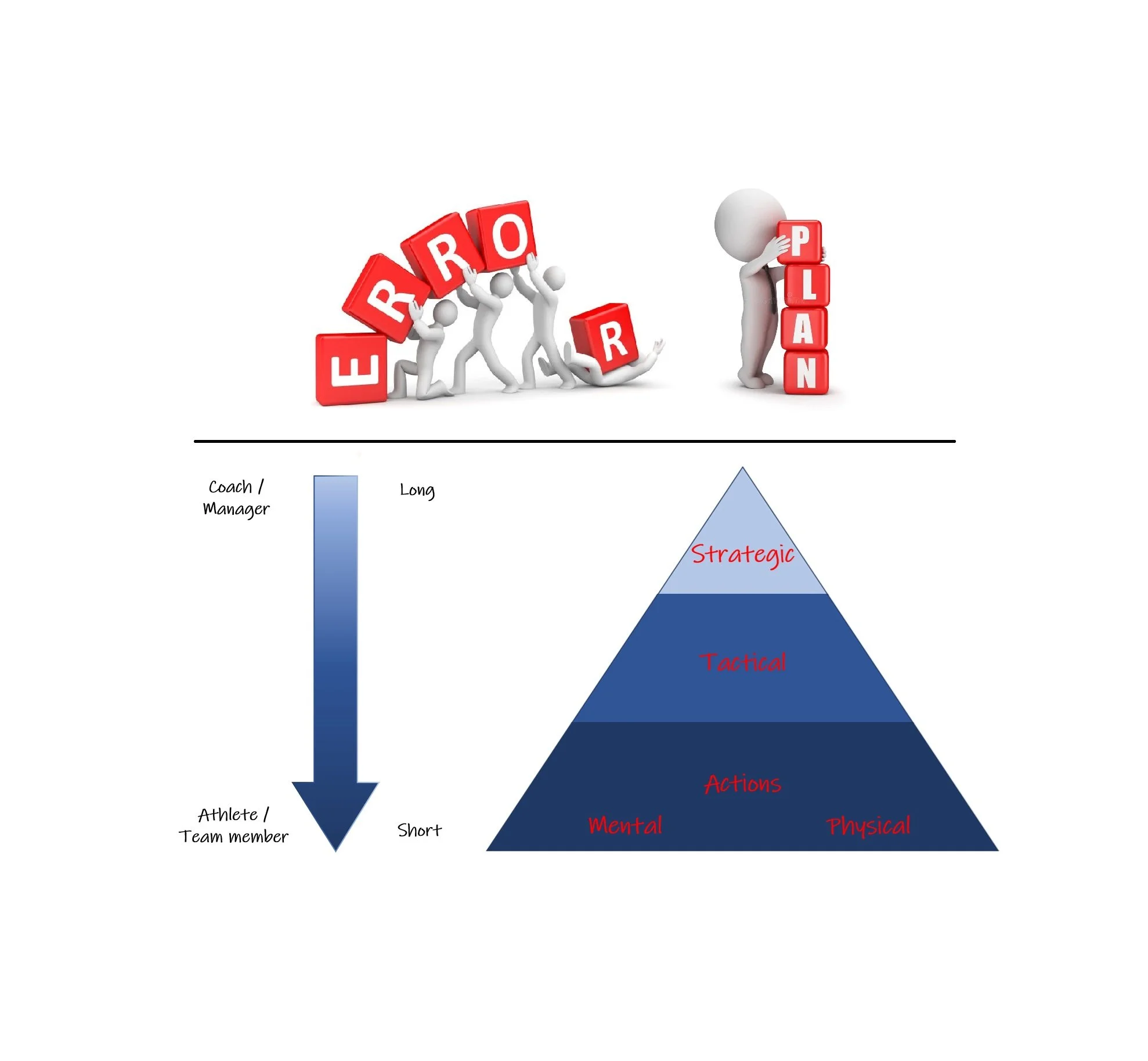

Errors & planning

Errors at the top of the pyramid (strategic) are the most influential, as they shape the framework within which tactical and action-level decisions occur. Conversely, errors at the bottom (action) are the most visible, but often the result of flawed planning above. Effective performance requires alignment across all levels, with clarity in long-term strategy, adaptable tactical decisions, and composed, well-rehearsed action on the ground.

This model reinforces that success is rarely about isolated execution—it’s built on layered, deliberate planning.

🔺 Top – Strategic Level (Coach / Manager – Long Term)

Focus: Vision, objectives, resources, and long-term plans.

Timeframe: Months to years.

Role: Coach, manager, or performance director.

Typical Errors: Poor alignment of goals and reality, unrealistic expectations, neglecting context or external factors (e.g. opponent trends, athlete development pace).

Impact: Errors here cascade down, making effective tactical and action-level decisions harder or impossible.

◼ Middle – Tactical Level (Coach & Athlete – Medium Term)

Focus: Game plans, session structure, positional roles, opponent-specific adjustments.

Timeframe: Days to weeks.

Role: Coach and athlete collaboration.

Typical Errors: Misjudged priorities, unclear instructions, poor adaptation to unfolding circumstances.

Impact: Leads to confusion or inefficient use of strengths, and can expose vulnerabilities in competition or training.

🔻 Bottom – Action Level (Athlete – Short Term, Real-Time)

Focus: Moment-to-moment physical and mental execution (e.g. decision-making, reactions, mindset, technique).

Timeframe: Seconds to minutes.

Role: Athlete or team member.

Typical Errors: Execution mistakes, lapses in concentration, emotional regulation issues.

Impact: Visible mistakes in performance; often symptom of deeper errors above.

-

![]()

Not always bad, just sometimes not ideal

In performance environments, there's often a significant gap between expectation and reality. We plan, train, and visualise success—but when reality hits, with its unpredictability, pressure, and external factors, things often unfold differently. This is where errors occur, not always because of poor skill, but because the outcome didn't match what was expected. Importantly, error isn’t always bad, and success isn’t always good.

Think of it like a cake: it might look perfect on the outside—beautifully decorated, polished, impressive—but taste awful once you bite into it. The result looks “good,” but the underlying process was flawed. Equally, a cake might come out wonky, uneven, or messy, but still taste amazing—the process was solid even if the result wasn’t pretty.

This analogy applies directly to coaching, leadership, and performance. Sometimes a “win” hides poor decisions or bad habits that were simply not punished. Other times, a “loss” exposes valuable truths, highlights areas for growth, and provides honest feedback that improves long-term outcomes.

Good isn’t always good, and bad isn’t always bad. The real measure of progress is not the surface result, but the quality of the preparation, the intention behind the action, and the learning that follows. Success comes not from avoiding error altogether, but from recognising what the error reveals and using that to bridge the gap between expectation and reality.

-

![]()

The secret recipe

Coaching and cooking are remarkably similar in their essence: both are creative, adaptive processes that begin with a plan but require skilled execution to produce a successful outcome. In this analogy, the coach is like the recipe designer—they provide the structure, the ingredients, and the ideal proportions. The coach defines the long-term vision, sets the framework, and outlines the key elements needed for success, including technical skills, tactical principles, physical conditioning, and psychological resilience. Like a recipe, this plan is based on knowledge, experience, and proven methods—but it is still theoretical until brought to life.

The athlete, like the chef, must then take these ingredients and interpret them in context. They are responsible for bringing the recipe off the page and into reality. A skilled chef knows when to trust the recipe and when to adapt—perhaps the ingredients are slightly different, the oven runs hot, or the dish needs a little more seasoning. Similarly, athletes must adjust their actions based on fatigue, the opposition, in-game dynamics, or unexpected challenges. Timing, intensity, feel, and decision-making all play a part. Even with the best preparation, the final performance often depends on how well the athlete or team can adapt and respond in the moment.

This highlights the important truth that having a good recipe is not enough. Success doesn’t come from rigidly following instructions—it comes from understanding the intention behind them and applying them skilfully under pressure. Just as a beautifully plated dish can still taste bland if cooked poorly, a team can look good in training but underperform in competition if the execution isn’t right. Conversely, a dish that looks messy might still taste incredible—just as a gritty, imperfect performance might lead to a crucial win or breakthrough.

In both coaching and cooking, the art lies in the blend of structure and instinct, of preparation and improvisation. The coach must continually refine the recipe based on feedback and evolving needs, while the athlete must develop the judgement and confidence to make smart choices under pressure. The end goal in both disciplines is not simply to follow instructions, but to create something memorable, effective, and ultimately successful. Just like a great dish, a great performance is the result of thoughtful design, personal mastery, and the ability to adjust and deliver in the moment.

-

Attitudes Are Contagious – Is Yours Worth Catching?

DescriptionOur attitude shapes how we show up—and it spreads. Whether consciously or not, others pick up on our mindset, effort, and standards. A positive, committed attitude can lift those around us, reinforce trust, and build collective momentum. On the other hand, complacency, corner-cutting, or apathy can quietly erode performance and morale. Attitudes are contagious, and the consequences of a poor one don’t just stay with the individual—they ripple across the team.

Imagine a group tasked with building a raft to cross a lake. Everyone has a role—tying barrels, securing logs, checking knots. One person, wanting to save time or energy, decides to take shortcuts. They tie fewer lashings, use weaker rope, or skim over checks, thinking, “No one will notice,” or “It’ll probably be fine.” On land, it all looks okay. The raft seems solid, neatly constructed. Their lack of effort is hidden behind the appearance of a finished product.

But then comes the test—the water. As the raft is launched, pressure builds. The logs shift, the knots slip, and suddenly, the raft begins to come apart. It’s not just the person who cut corners who ends up in trouble—the whole team is affected. Even those who were meticulous and did everything right now find themselves soaked, exposed, and scrambling, all because one person decided that “good enough” was enough. The shortcuts, invisible on dry land, become painfully obvious under real pressure.

This is the reality of attitude. When things are calm, it's easy to mask poor effort. But when it’s time to perform, to lead, or to deliver under pressure, the truth reveals itself—and it affects everyone, not just the individual. That’s why your attitude matters. Not just for your own success, but for the safety, trust, and performance of the whole team. If others adopted your approach, would it hold things together when tested—or would it weaken the very thing you're trying to build? Attitudes are contagious—make sure yours is one worth catching. goes here

-

![]()

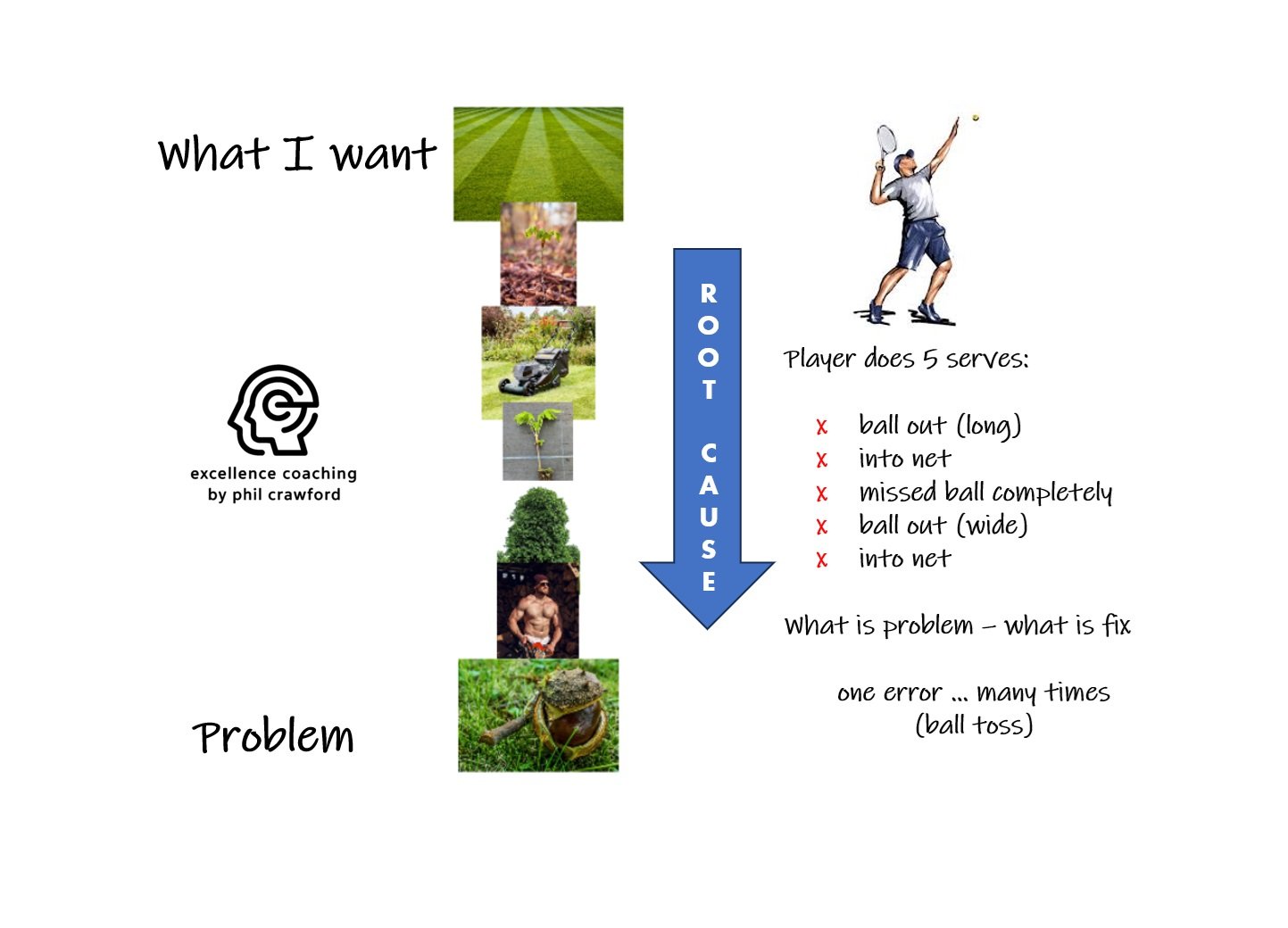

What is the actual issue

Wanting a lawn of lush, striped green grass is a clear and simple goal—but when horse chestnut trees begin sending up unwanted shoots, the surface problem becomes obvious: saplings spoiling the lawn. The instinct might be to just cut them off at ground level. It’s quick, it’s tidy, but the problem comes back. A little deeper and you realise the roots are still alive underground, fuelling the regrowth. So perhaps the solution is to dig out the roots—but even then, the real issue continues. Why? Because the source of the problem is still there—the tree itself.

But here’s the twist: the tree can’t (or won’t) be removed. You don’t want to—or legally can’t—cut it down. That means the real root cause is upstream of even the roots; it’s the falling conkers, quietly dropping into the grass, embedding unnoticed, and then sprouting into a full-blown issue months later. So, if the tree stays, what can be done? The solution lies not in repeatedly cutting or digging, but in early intervention: either stop the conkers falling in the first place (containment or mitigation), or pick them up as soon as they fall—before they embed, sprout, and multiply.

This perfectly illustrates the essence of effective problem-solving. Surface-level fixes only provide temporary relief. Digging deeper helps, but even then, if you haven’t truly understood the source and the timing of the problem, it will persist. Often, sustainable change comes not just from finding the root, but from identifying the trigger and acting early, when the problem is small, simple, and manageable. In coaching, leadership, or life, it’s not always about removing the tree—it’s about learning how to manage its effects before they grow into something harder to control.

Root cause analysis is a critical process used to identify the underlying reasons behind a problem or failure, rather than just addressing its symptoms. In performance, coaching, business, or safety contexts, it’s easy to focus on what went wrong at the surface level—a missed goal, a failed task, or an error in judgment—but without understanding why it happened, solutions tend to be short-term and ineffective. RCA seeks to dig deeper, asking questions like “What led to this?” and “What was happening before this occurred?” to trace issues back to their origin. This might involve looking at systems, processes, communication gaps, planning flaws, or even mindset and environmental factors.

Identifying the true cause is essential because it ensures that the right thing is being fixed. For example, punishing an athlete for a poor pass might address the immediate error, but if the root cause was unclear communication, lack of tactical understanding, or fatigue from overtraining, the problem will resurface. By solving the real issue, performance can improve sustainably and future errors can be prevented. Whether in coaching, leadership, or operational settings, RCA helps shift the focus from blame to understanding, enabling smarter decisions, better planning, and long-term improvement. Without it, effort and energy are often wasted treating symptoms while the core issue continues to undermine progress.

-

![]()

Do you look or see

There’s a large and powerful difference between looking and seeing—and understanding it can transform how we learn, lead, and perform. To look is to direct your eyes toward something. It’s passive. You might look at a map, a person, or a problem and register that it’s there—but that doesn’t mean you truly understand it. To see, however, is to notice, interpret, and make meaning. Seeing is active, intentional, and reflective. It involves attention, context, and curiosity.

In high-performance environments—whether in sport, leadership, or adventure—the gap between looking and seeing is often where mistakes happen. A coach might look at an athlete and assume they’re fine, but someone who sees might notice a subtle shift in posture, hesitation, or fatigue. A mountaineer might look at a slope and see fresh snow, but only by seeing the angle, layering, wind patterns, and recent temperature change can they assess avalanche risk. Looking gives us information. Seeing gives us insight.

The same applies in communication. You can look someone in the eye and still miss what they’re really saying. To truly see requires presence—not just visually, but mentally and emotionally. It’s the difference between reacting and responding, between walking past a problem and recognising an opportunity to solve it. Developing the ability to see rather than just look is what separates those who move through the world on autopilot from those who observe deeply, think critically, and act wisely.

In short, we all look—but the ones who grow, lead, and make an impact are the ones who truly see.

-

![]()

Take Time to Find the Real Question

One of the most common reasons people struggle to find the right answer is because they haven’t yet identified the right question. We often throw effort, time, and energy at solving a problem, only to discover later we were tackling the wrong thing. The real issue wasn’t misunderstood—it was unseen. And that’s not due to ignorance or lack of ability, but because, quite simply, we only know what we know.

This is where the Johari Window offers powerful insight. It breaks awareness into four areas:

Open – what both you and others know about you,

Hidden – what you know, but others don’t,

Blind Spot – what others know, but you don’t,

Unknown – what neither you nor others know yet.

When trying to solve a problem or grow personally or professionally, we often operate only in the "open" and "hidden" spaces. But the real insights—the root causes, limiting beliefs, or missed opportunities—often sit in our blind spots. And because they're outside our current awareness, we can’t even form the right question to explore them.

This is why feedback, coaching, and honest conversations are so important. Yet they’re uncomfortable. Asking someone to help you see what you can’t is vulnerable. It means admitting you don’t have all the answers, and worse, you might not even be asking the right things. But this discomfort is also where clarity lives. It’s the only way to uncover what truly needs attention—to move from surface-level fixing to deep, meaningful change.

Just like a map is useless if you don’t know your current location, solutions are meaningless without the right question to anchor them. So pause. Reflect. Ask yourself: What am I really trying to solve? What might I be missing? And most importantly: Who can help me see what I can’t? Because sometimes, the breakthrough you need doesn’t come from trying harder—it comes from asking smarter.

-

![]()

Why would I vs Why would I not

Reframing your thinking from “Why would I?” to “Why would I not?” naturally leads into the mindset of growth through challenge—stepping beyond what's comfortable in pursuit of development.

Pushing yourself isn’t about reckless risk or relentless pressure; it’s about intentionally choosing to grow by moving into what’s known as the stretch zone—the space between comfort and panic. In the comfort zone, everything feels safe and familiar, but growth is minimal. You can operate smoothly, but you're not learning anything new.

The panic zone, on the other hand, is overwhelming—when the challenge feels too big, learning shuts down, and fear takes over. But in the stretch zone, where you feel challenged but still capable, real development happens.

Consistently stepping into your stretch zone builds resilience, skill, and confidence. You become more adaptable, more self-aware, and better equipped to handle future pressure. The benefits go beyond technical growth—you start to rewrite your internal narrative. “I can’t” becomes “I can try,” and eventually, “I’ve done it.”

The more often you lean into that discomfort, the more your stretch zone expands, and the less intimidating growth becomes. Framing the decision as “Why would I not?” pushes you to evaluate whether your resistance is based on real limitations or just the discomfort of the unknown. And in doing so, it helps you make braver, smarter choices that move you forward. Growth is rarely comfortable, but it’s always worth it—and sometimes all it takes to begin is asking the right question.

-

![]()

We all play a part

In any successful team, we all have different roles, each with its own value—and it’s the coordination of these roles, not just individual effort, that drives performance. A powerful example of this is seen in dragon boating. In a dragon boat, every paddler has a job: some set the pace, others provide power, and some focus on timing and rhythm. At the front, the drummer provides a unifying beat, helping the team stay in sync. At the back, the helm steers the boat, making sure all the power is directed toward the intended path. Even with strong paddlers, without coordination, the boat will drift, stall, or go in circles. Everyone must work in harmony, pulling in the same direction, complementing each other’s strengths.

This mirrors how Belbin’s Team Roles work in high-performing teams. Belbin identified nine key roles—from implementers and shapers to coordinators, thinkers, and completer-finishers—each essential to team success. Like in a dragon boat, no single role is more important than another; it’s about balance and clarity. You need creative minds to innovate, action-oriented people to drive progress, and detail-focused individuals to ensure nothing falls through the cracks. Just as a dragon boat fails without timing and leadership, a team loses direction without coordination, understanding, and shared purpose.

Ultimately, team success depends not just on effort, but on alignment—on each person understanding their role, recognising the strengths of others, and trusting the leader to steer toward a common goal. When everyone contributes their unique strengths in sync, the team moves forward with speed, purpose, and unity.

-

![]()

OODA loop

Description goes hereIn sport, just like on the battlefield, the OODA Loop—Observe, Orient, Decide, Act—is the foundation of performance under pressure. Every moment of competition is a dynamic cycle where athletes and teams are constantly processing information, adapting, and executing. Success doesn't just come from physical ability—it comes from the speed and quality of decision-making. The team or athlete that can move through the loop faster and more accurately gains a decisive edge.

Consider a fast-paced game like volleyball, rugby, or football. A player must first observe—read the opponent's formation, spot movement, track the ball, or sense changes in momentum. Then they must orient—interpreting what that information means in the context of their own positioning, team strategy, strengths, and weaknesses. This step is personal and situational. Two players can see the same play, but interpret it differently depending on their experience, role, and confidence.

Next comes decision—choosing whether to pass, press, shoot, hold, or reposition. This must happen in split seconds, often with incomplete information. Finally, the athlete must act—executing the chosen move with precision and timing. If they hesitate, the window of opportunity closes. But if they act before their opponent can respond—they control the play.

In team sport, the side that can run this loop more effectively collectively—where everyone is reading, adapting, and acting in sync—dictates the tempo and forces the opposition to react, rather than act. Over time, this creates pressure, forces mistakes, and builds momentum.

Ultimately, sport is not just about talent or strength—it’s about processing speed, decision-making clarity, and coordinated execution. The faster and more fluently an athlete or team can cycle through the OODA loop, the more likely they are to dominate. In tight contests, it's not just the strongest who win—but those who think faster and act first.

-

Ready or Really ready

In ski touring, the difference between being ready and being really ready can be the difference between a great day in the mountains and one that quickly unravels. Being ready often means your boots are on, your skins are cut, your bag is packed, and you've glanced at the forecast. It’s the checklist version of preparation—on the surface, everything looks in order. But being really ready starts well before the first step. It begins at home: studying maps, checking avalanche bulletins, planning multiple route options, and packing with intention—not just for efficiency, but for resilience.

Ski touring isn’t a controlled environment. Weather shifts. Snowpack changes. People fatigue. Being really ready means you’ve anticipated challenges and equipped yourself physically, mentally, and emotionally to handle them. It’s knowing how your body feels at altitude, when to push and when to pause, how to navigate white-out conditions, or what to do if someone in your group takes a fall. It’s about building in margins, not relying on luck.

Someone who’s just ready might look confident at the trailhead but be overwhelmed when conditions tighten. The person who’s really ready carries quiet confidence—because they’ve taken ownership of every layer of preparation. They’ve visualised the route, prepared for worst-case scenarios, and are ready to adapt. They don’t just want the summit—they’re prepared for the entire journey, including the descent. In ski touring, like in life, being ready gets you to the start. Being really ready gets you home—safely, confidently, and with lessons you’re proud to carry into the next challenge.